- Home

- West Camel

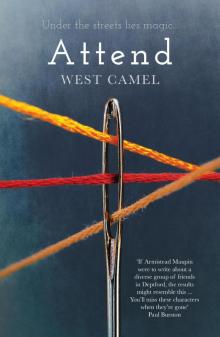

Attend

Attend Read online

Attend

WEST CAMEL

For the original Deborah Wybrow (1732–1834)

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1: Anne

Chapter 2: Deborah, 1913

Chapter 3: Sam

Chapter 4: Anne

Chapter 5: Sam

Chapter 6: Deborah, 1913

Chapter 7: Sam

Chapter 8: Anne

Chapter 9: Deborah, 1922

Chapter 10: Sam

Chapter 11: Anne

Chapter 12: Sam

Chapter 13: Anne

Chapter 14: Deborah, 1930

Chapter 15: Sam

Chapter 16: Anne

Chapter 17: Sam

Chapter 18: Deborah, 1941

Chapter 19: Sam

Chapter 20: Anne

Chapter 21: Sam

Chapter 22: Anne

Chapter 23: Sam

Chapter 24: Anne and Sam

Chapter 25: Anne and Sam

Chapter 26: Anne and Sam

Chapter 27: Deborah, 1941

Chapter 28: Anne and Sam

Chapter 29: Anne and Sam

Chapter 30: Deborah, 1950

Chapter 31: Anne and Sam

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

Chapter 1: Anne

Anne pulled at the door, but it resisted; it clung to the jambs. She hoped no one was passing on the balcony outside, seeing that she couldn’t even get out of her own home.

She tugged again and recalled struggling like this once before. When Mel had locked her in.

He’d grabbed her as she’d made a dash for the front door of their flat. Held her against the wall, his heavy forearm at her throat; searched her pockets for her keys and the money she’d stolen from his wallet to buy herself a hit.

‘Now look after your fucking kid,’ he’d shouted as he locked the door from the outside, his face a dirty blur in the frosted glass.

Julie had wailed in the next room – the insistent keen of a six-week-old. What was it – eighteen years ago? The sound still rasped.

Anne’s hand slipped and she grazed a layer of skin off the knuckle of her thumb. She took a breath and looked down at the key in her palm, its grooves and notches clean and new. Mel was long gone, she was alone and this door was just a bad fit. She tried pushing her toe under its bottom lip and pulling the handle upward. With a bit of a twist it opened.

She stepped out into sunlight and the smell of roasting meat. Sunday. Her mother would be busy with the dinner right now – hot, banging pots. Perhaps she should walk over there – have something to eat, help with the washing-up. But Julie would be home with the baby. They wouldn’t want Anne there, spoiling things.

As she descended the three floors to the courtyard, she heard booming voices and shrieking kids. The Nigerian family on the ground floor had just arrived back from church. Anne nodded to them as she passed – the children in neat suits and dresses, the men smart, and the women tall in their hot-coloured wrappers and stiff headscarves.

‘Hello, how are you settling in?’ asked the mother, her children swinging at the ends of her long arms.

‘Not bad, thank you. Getting there, you know.’ But Anne kept moving, conscious of her mousey, messy hair, her drab jeans and scuffed trainers.

She hurried on out of the courtyard, not sure now whether she would call her mother. But waiting at the crossing on Church Street, she reminded herself why she had come back, clean, to Deptford. She pulled out her mobile phone; no credit. There was a phone box on the other side of the road – she would call from there and invite herself to dinner. She would make herself sound cheery and relaxed.

Rita answered loudly, but seemed to lower her voice when she realised it was Anne.

‘Oh, hello, love. What’s up?’

‘Nothing, just settling in, you know.’

‘Need anything doing?’

‘I’m OK, I’m doing everything myself.’

‘Oh yes? Well, don’t be knocking back help when it’s offered; you don’t know when you might need it.’

Anne gripped the phone’s stiff metal cord. ‘How’s everything there?’

‘Alright. We’re sitting down to dinner in a minute.’

‘Oh right. I was thinking I could come over, if you don’t mind. I just fancy a roast.’

Rita paused for a moment. ‘I’d like to say yes to you, love, but…’

‘Don’t worry, not enough to go round?’

‘Well, that, and, well, Mel’s here.’

Anne dug her nail into the graze on her thumb. ‘Come for his lunch most Sundays, does he?’ She knew it was the wrong thing to say as soon as the words were out.

Rita was quick to react. ‘No, but he’s been to see his daughter and grandson a lot more than you have.’

‘I want to come now, don’t I?’

‘Well, I didn’t know that. You wouldn’t want to be here with him anyway, would you?’

‘No, I fucking wouldn’t.’

‘Well there you are, then. What can I do?’

‘You just think he’s some fucking saint and I’m the only one that fucked up.’ Anne heard her voice scudding away from her. ‘And Julie thinks the sun shines out of his fucking hole. If she knew what it was like when she was little—’

Her mother interrupted, hard and quiet. ‘She don’t, Anne. But I do. And I also know that it was me that looked after her when you was off sticking yourself full of that shit. So don’t start.’

Anne was silent. She heard her own breath in the handset. A train rumbled along the viaduct above her.

‘Go on then, got any more?’ said Rita. The baby cried in the background.

‘No, Mum.’

‘Right, then.’

‘Bye.’

Anne thumped the wall of the phone box. Everything was clenched, her throat was tight. She tried to slam the door as she left the box, but the spring insisted on closing it slowly. Mel must be sitting down at her mother’s table now, his fists tight around a knife and fork, a napkin tucked into his shirt, his heavy jaw steadily chewing through the meat. While she stood here alone, under the railway arch, not sure where to go. The noise of a massive, empty lorry drove her out, fiercely picking at the hem of her coat.

She wanted a fix, and had to shake her head and mutter ‘no’ out loud – she was beyond that now. She turned into Crossfield Street, her gaze lowered to the patches of old cobbles appearing where the tarmac was wearing away.

She slowed down; there was a bench ahead – she could sit down there and calm herself. It was on the edge of a green space that was criss-crossed oddly by humps and half-walls – left over from before the war, she always supposed. Beyond it was the white church where she had been married to Mel. Kathleen – Mel’s sister, and her oldest friend – had been bridesmaid. That had been the best part: her and Kathleen in their dresses.

She looked up at the church tower, its columns and scrolls rising above the uglier buildings around into an almost irresistibly sharp needle. The intricate gold clock below it always surprised her by telling the right time. And, as she looked, the bell began to chime.

When she looked down, she saw someone else was sitting on the bench: an old woman in a dark-grey woollen skirt and shawl, a grey bag placed beside her. She was bent over slightly and what looked like a white sheet was spread across her lap. Anne’s step faltered – she could not work out where this person had appeared from. The woman glanced up as she passed, and Anne, attracted by the clean, open face and wave of white hair, allowed herself to smile and nod. But rather than returning her smile, the woman’s face tightened in shock and she clutched at the edges of her shawl. Anne saw something drop from her hand and bounce onto t

he ground, leaving a twisting trail behind it. Turning her head back, Anne saw that it was a reel of white thread. The woman made no effort to pick it up, but stared open-mouthed as Anne walked away. Anne shook her head again, wondering why she had bothered coming back to Deptford.

She reached the junction with the High Street and turned back into the churchyard, where there were more benches among the graves and rose bushes. She had always found a little peace here. When she had rowed with her mother, or Mel or Kathleen, she would come and sit on the stone caskets or, most often, on the curved steps under the church’s semicircular porch.

Now, as she lowered herself onto the top step, she heard the swell of voices from the service on the other side of the doors. The hymn’s tune was familiar, but the words escaped her for the moment, and she couldn’t resist a growing feeling that, after the long, meandering journey to get herself clean, she was back where she had started. She leaned against the pillar behind her and tried to tell herself that things were different now: she hadn’t taken smack in two years; Julie was grown up and had her own baby; she and Mel had divorced long ago. But she still hadn’t seen Kathleen; and he was at her mother’s table while she was stewing on these same cold steps.

The voices had been quiet for several minutes when the old woman who had been sitting on the bench in Crossfield Street came in through the churchyard gate. She strolled slowly down the path, making a show of looking at the graves on either side, but all the time sneaking glances up at Anne. Her clothes and her bag were the same colour as the rain-stained stones. When she was just a few yards away, she seemed to realise that Anne was watching her, drew her short figure up a little and looked Anne full in the face, her lips parted and her blue eyes wide. There was something slightly desperate about her expression that made Anne move around on the step, but she held the woman’s gaze and, at this, the woman approached more purposefully until she stood nearly at Anne’s feet.

‘Good morning.’ She held her hands neatly over her belly. ‘I think I might have taken your seat over there.’

‘Don’t worry about it, I’m alright here now.’

‘Lovely spot, isn’t it?’

Anne nodded, wondering whether she didn’t want the woman to go away.

‘It’s one of the few bits of the old Deptford left.’

‘Well, it’s changed a lot over the years.’ But Anne wasn’t sure this was really true.

‘You know Deptford, then?’ The woman stared intently at her now.

‘I grew up around here. But I’ve been away for a few years; just moved back a couple of weeks ago, actually.’

The woman raised her eyebrows. ‘I’ve lived here most of my life.’ She glanced around her, then back at Anne. ‘Have you…’ she began, and her face flicked between a smile and an interested frown, as if she wasn’t sure which to use. She stopped, smoothed her shawl and spoke again, ‘Have you seen me before?’

Anne didn’t know how to answer. If the woman had said ‘Don’t you remember me?’ she could have said ‘no’ and apologised. She wriggled out a reply: ‘I may have done, but it’s been years since I lived here.’

The woman shook her head, ‘I didn’t think you had. Doesn’t matter. May I sit?’

Anne nodded, and the woman climbed up and sat close beside her with a satisfied sigh. It would be difficult to leave now, Anne thought, even if she had something to leave for. But the woman seemed harmless enough; she didn’t smell bad, and there was something about her – about her clothes, her voice, her grey cloth bag. I can have a chat with a lonely old woman, Anne told herself.

‘Were you going inside?’ Anne asked. ‘Only I think the service has already started.’

‘No, I’m far too old for all that. I was christened in here, a long, long time ago. But it’s just a distraction now.’

‘I remember my nan saying that the older she got, the more she thought she should go to church, read the Bible and all that. “Make an impression for him upstairs,” she used to say.’

‘Well, that’s another way of looking at it.’ The woman’s clear eyes scanned the graves. Her skin was surprisingly smooth. ‘Don’t get you there any quicker, though,’ she said, and looked back at Anne with her mouth a little open, so that Anne could see the tip of her tongue. The step began to feel uncomfortable again.

‘Perhaps you knew my nan; she lived here all her life too.’

‘Is she dead?’

‘Oh yeah.’ Anne frowned – she thought that had been clear. ‘She died years ago.’ She felt her face droop – recalling her nan brought her swiftly to her mother, and so to Julie and then to Tom, the baby: a smooth chain in which she was the snag. She fell to stewing again.

After a moment, the woman shuffled slightly and announced in quite a different voice, giving encouraging smiles between each phrase: ‘From here, you can see where I was born.’ She pointed towards Crossfield Street. ‘The old house I lived in when I was a child – just through there, you see it? Number thirty-six.’ Anne looked the other way and saw the backs of the ancient houses of Albury Street. ‘Where I lodged as a young woman, above one of the shops,’ she indicated the High Street ahead of them; ‘and where I would very much like to end up!’ She presented the graves to Anne with a prompt little movement of her hand and let loose a trill of laughter. For a second, Anne expected her to try to link arms, as her grandmother had liked to. She forced herself to laugh too, and the tickling in her throat seemed to pluck her out of her slump.

‘Where do you live now?’

‘Over by the creek,’ the woman flapped her hand behind them.

‘That’s where I live – the estate. You too?’

‘No, but near there. Perhaps we could pay each other a visit some time.’ And she touched Anne’s hand with her own – a combination of silky-skinned fingers and hardened tips.

As Anne tried to work out a response, the doors behind them swung open and the congregation emerged, shaking each other’s hands as they spread across the steps. They wove around Anne, giving her sideways looks, but the old woman had to stand up quickly to avoid being trodden on.

The priest moved from person to person, nodding and smiling, and caressing his embroidered stole. And before Anne had a chance to get away, he was standing over her, displaying his yellow teeth. ‘Were you wanting to come in for the service? There’s another one this evening if you can wait.’

Anne rose awkwardly. ‘Oh no, I was just sitting here.’

‘Well, feel free to attend – we always welcome newcomers.’

‘Thank you, Father,’ she managed, and then, not sure what else to say to his long grin, she turned to draw the old woman in. But he had already gone back into the church, without a word or a glance at her.

‘He didn’t even say hello to you,’ Anne said. ‘That was a bit rude.’

‘He didn’t see me.’ The woman beamed. ‘Very few people do.’ She picked up her bag, the white cloth swelling out of it like rising dough. ‘But you do – so I’ll tell you my name: Deborah.’ She put her hand out.

Anne looked down at it and, now they were standing on the same step, she was struck by how small the woman was – almost the size of a child. And then she realised what the hand meant. She gave it a gentle shake. ‘I’m Anne.’

‘Very pleased to meet you, Anne.’

Anne began to turn away, thinking it was time to go home now, but Deborah held on to her. ‘Would you like to take a turn around the church with me?’ Her grip was surprisingly strong – Anne would have to pull sharply to get her hand back.

She hesitated before replying; but the sunshine was warm on her back and at home there was just TV and cups of tea. ‘Go on, then,’ she said.

Deborah dropped Anne’s hand and drew her bag up to her chest. ‘I might just tell you a story too. If you’re interested.’

‘Why not.’

They descended the steps and ambled along the path that encircled the church, passing into its shadow then back into the spring sunlight. By the time

they returned to the porch, the church doors were closed and the graveyard was empty. Deborah slung her bag on a large stone casket, placed a foot on the base and, with a small, certain effort, pushed herself up onto it.

‘Come and sit.’ She patted the lid and began to pull the white sheet out of the bag.

Anne perched on the opposite end and watched while Deborah opened the sheet out and floated it onto the casket like a tablecloth. She saw now that it was embroidered all over with tiny white stitches, which were nearly invisible against the white of the sheet itself.

‘It’s beautiful. Did you do it all yourself?’ A needle was neatly pushed into the far end and a loop of thread hung down into the grass at their feet.

‘I did.’ Deborah smiled, then looked down into the pattern, her shawl falling back off her head. She inhaled and spoke at the same time, ‘Many, many years of work.’

Anne put a hand on her end of the sheet and felt the tickling texture of the stitches. ‘So tell me this story, then.’

Deborah settled her shoulders; then, pulling a section of the sheet onto her lap and circling her fingertips over it, she began.

Chapter 2: Deborah, 1913

‘That day in 1913, the day I found the strip of cloth with the motif stitched onto it – the day she gave it to me, I should say – no one seemed to be paying me the slightest bit of attention. I thought it was because they wanted to be rid of me. I was seven – far too old for the Hospital for Infants in Albury Street. I’d heard Mrs Clyffe say as much to Sally when we were walking back from church the previous evening.

‘“I shall have to be thinking of where to send Deborah, you know. I’ll have the Institute Ladies on my back otherwise. We’re not really supported for the grown ones.”

‘She hadn’t meant for me to hear her, but I did; and that entire evening, while she read aloud from the Illustrated London News, I thought about what I’d heard her say.

‘Mrs Clyffe took the Illustrated London all the years I knew her, and after supper on Sundays, she would read out parts she thought suitable to the other staff at the hospital. Being older than the other children, I was allowed to stay up and listen too.

Attend

Attend